Features 14.03.2024

Features 14.03.2024

First things first: If specifying the make of my car in the title comes across as crass, that is not my intent. I did it because it’s relevant to the way it was stolen and because Mercedes have given me an interview for this feature. Perhaps this disclaimer is unnecessary, but I felt it was important to note. Also, for the record, this was the first half-decent car I’d ever owned. I’m not fancy!

As a cybersecurity journalist of 18 years, I’ve written and edited multiple articles on car hacking over time. I even interviewed the great Charlie Miller about the topic once upon a time in America. But, I’ve been guilty of what so many people are: learning about cyber threats and allowing myself to feel detached from the reality of it, therefore falling into a false sense of ‘it won’t happen to me’ security. What a classic fool.

I’m no different to the hundreds of thousands of people who have their car stolen every year in the UK. No different except when it happens, I have an entire profession to call upon to share their expertise and offer insight and explanation.

According to the latest DVLA figures, a car is stolen approximately every eight minutes in the UK.

The Office of National Statistics analysis shows that 397,264 cars were stolen in England and Wales between October 2022 and September 2023. This number is far greater than commonly reported by the media, but I verified it with ONS, who confirmed that my reading of the data is correct.

The most stolen car is Land Rover, with Mercedes ‘earning’ silver and Ford grabbing bronze; medals that no manufacturer wants to receive.

Statistics on the percentage of vehicles recovered vary depending on the data source, but few claim it is greater than 20%.

So that’s the grim reality of car theft in the UK. But how are these cars being stolen without leaving any sign of forced entry, vanishing silently in the night?

I drove a Mercedes-Benz GLC 220 AMG Line Premium D, a relevant detail as it had keyless entry and engine start. I was later informed by the detective assigned to my case that six cars of a similar calibre were stolen from within a one-mile radius over two evenings, and the view of law enforcement was that it was likely an organised crime group travelling to the area (Oxfordshire) from London or Birmingham.

“Six cars of a similar calibre were stolen from within a one-mile radius over two evenings”

Finding my driveway carless one rainy morning in February was quite a shock. Both car keys were exactly where I’d left them. My partner confirmed that he had not moved my car (yes, I called to check!), and there wasn’t a single shard of glass or sign of forced entry on the driveway (a private driveway tucked away in the corner of our sleepy cul-de-sac. So private, in fact, that taxi and delivery drivers often struggle to find us.) It took about five minutes for me to reach my own conclusion: my car had been hacked. But was it?

“I’d say so, yes,” responds Graham Cluley, host of the Smashing Security podcast. “In its broadest sense, hacking is gaining unauthorised access to something, and the scumbags who stole your car did just that, by exploiting a flaw in its entry system.”

David Rogers is the CEO of Copper Horse, specialists in connected car security. “It’s almost certainly car hacking,” he agrees. Many others interviewed for this article wasted no time confirming my car had been hacked.

Adam Pilton has a different stance. He spent 15 years in law enforcement as a police officer and a detective, and is now a senior cybersecurity consultant at CyberSmart. “While the term car hacking might conjure images of a complex and sophisticated attack, based upon the fact that six cars were stolen within the area over two nights, I believe that the most likely attack used was a relay attack, a far simpler and more effective method.” That raises the question: is a relay attack not a hack? More on this later.

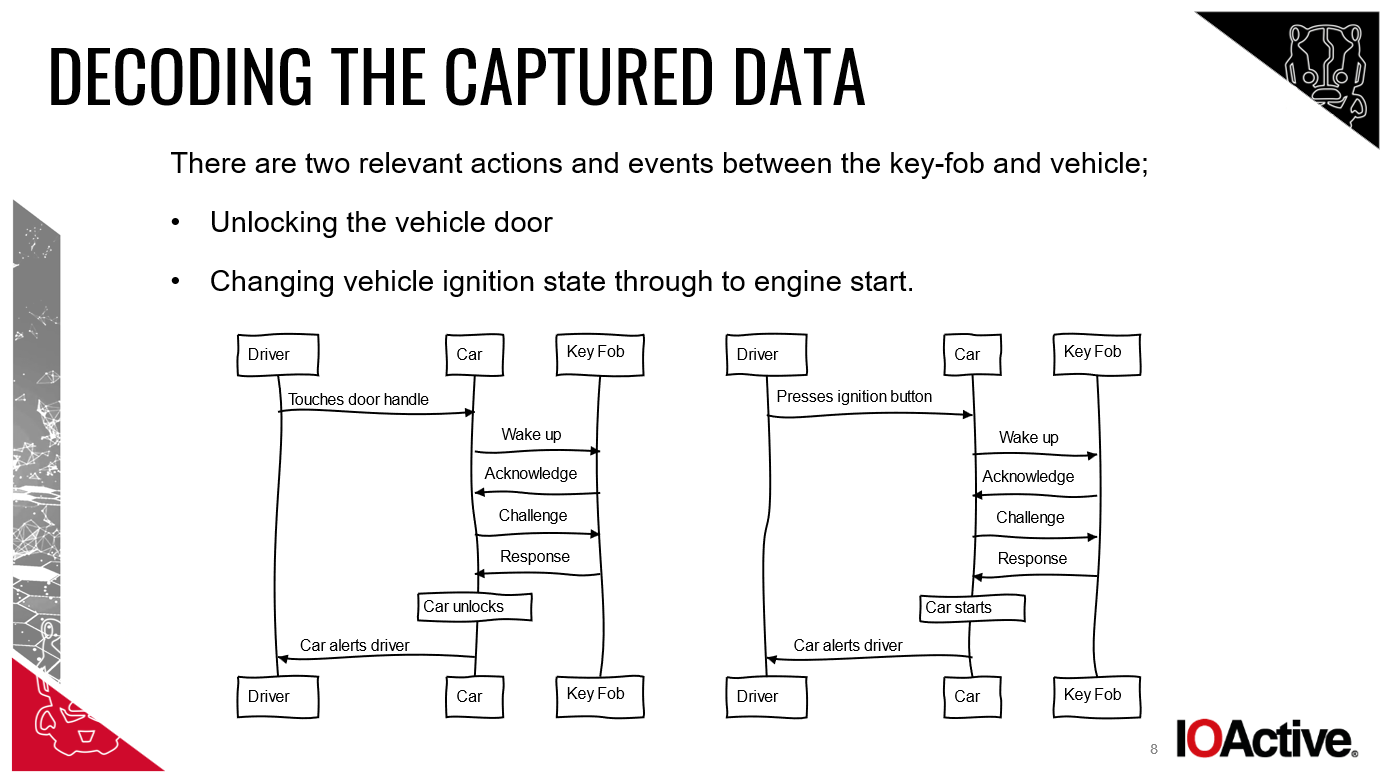

Ivan Reedman is the director of secure engineering at IOActive. He injects a bit of a reality check: “If we look at a typical definition of hacking as ‘the gaining of unauthorised access to data in a system or computer,’ this would not be classified as a hack. The criminals gained unauthorised access to the car, yes, but not to any data, so I would argue this is a theft vs. a hack.”

In cybersecurity journalism, there are often several contrasting perspectives on attack methodology. However, the eight experts I interviewed for this feature were unanimous in their hypothesis: “Your car was stolen by relay attack.”

My car had ‘passive entry passive start’, known as PEPS. In non-technical talk, as long as I had the key on me, I could get into the car and start it without pressing any buttons or even touching the key.

“Relay attacks are one of the simplest attacks, requiring no [technical] knowledge or secrets” Ivan Reedman

Chris Pritchard is a principal adversarial engineer working for cybersecurity consultancy Lares. He explains the thieves used “a tool and aerial to relay the signal broadcast between your contactless key and the car. The car is tricked into thinking the key is close and unlocks the door.”

“They would have used two devices to carry out the attack,” adds William Wright, CEO at Closed Door Security. “One device would be placed near your house to pick up the signal from the key fob, even from a distance and through walls. The other device would be positioned next to the car to relay that signal.”

Typically, the relay device only needs to be within 10-15 metres of the key to work. And according to several sources, it can be done in around 30 seconds.

Reedman adds: “When the device [closest to the keyless key] relays the fob’s signal directly to the car, it allows the thieves to get in and drive away immediately. Such an attack functions as a range extension attack, increasing the range at which the PEPS functionality operates.”

“Relay attacks are one of the simplest attacks, requiring no [technical] knowledge or secrets,” continues Reedman. He demonstrated a relay attack to the BBC using equipment he built using an audio amplifier from Maplin, AA batteries, and copper wire. “I demonstrated how quickly I could unlock and drive away the Mercedes AMG owned by the BBC One Show producer.”

So, we now know how they got into and started my car, but how did they continue to drive it after the vehicle discovered the ‘key was not present’?

“Once the engine is started, most vehicles will alert the driver that the key is not present but will not turn the engine off. Once started, the engine will run until stopped, [at which point] the thieves assign a new key to the car and disable your key,” explains Reedman.

“The car isn’t going to suddenly refuse to drive if it can’t see the key anymore,” adds Cluley. “That would be dangerous if the key battery expired, for instance. But the car may refuse to be restarted if turned off.”

Access via relay attack can only take the criminals so far (as far as they drive it until the engine stops). At that point, they need access to the on-board diagnostics (OBD). “Access to the OBD will trigger the car into starting by using other devices,” explains Rogers. “Once the car is fooled into thinking the driver has legitimate access, there’s no reason to prevent driving.”

Pritchard explains that the criminals would likely have had an OBD programming tool. “It’s a little port normally underneath the steering wheel, just to the right. Garage mechanics use it for diagnostics and resetting warning lights, for example.” Pritchard is speaking from experience. ”When my Audi was stolen to use in an armed robbery, they broke in and programmed a new key with an OBD tool so they could open, close and start the car as needed. There’s a good chance something similar happened here,” he guesses.

I put the idea of key cloning to the experts interviewed for this feature but that returned shaking heads all around. “I suspect nothing as complex as a key cloning attack,” Reedman says.

The same response was received when I questioned the likelihood of a Flipper Zero attack.

Initially, when I posted about the incident on Twitter (yes, I know it’s technically now X), I had multiple experts suggesting that a Flipper Zero attack could have been at play. @Mayples wrote: “Many cars are prone to key fob IR range dupe/focus. They use antenna and a Flipper Zero to replicate the key inside car, unlocks often from antilock-in and then they duplicate the fob into the flipper and drive off (sic).”

@rik-ferguson wrote: “I’m thinking Flipper Zero or equivalent…Flipper Zero is incapable of rolljam attacks, but is capable of unlocking older cars that do not have this feature (simple relay) or of recording rolling codes out of range of the vehicle for subsequent immediate use.”

However, interviewees for this feature, armed with the whole story, declared the involvement of a Flipper Zero “highly improbable.” These are Reedman’s words, but the sentiment was shared by all.

“As much as the Canadian government would love to pin it on a Flipper, this is not a Flipper attack,” says Pritchard. He refers, of course, to the Canadian government ban on the pocket-sized devices early in February 2024. Retailing for around £150, Flipper Zeros can check for vulnerabilities in wireless networks, clone access cards and send and receive infrared signals and radio frequencies. A powerful tool which the Canadian federal government claimed is instrumental in the increase in auto theft. “The Flipper does have a lot of capability all in one small tool, but not this,” insists Pritchard.

Now that I’ve established how my car was hacked, I turn my attention to who did it and how they acquired the skill or equipment to do so.

“The technique is well known by car thieves, and there’s plenty of information about how to do it online,” explains Cluley.

“Car theft equipment is astonishingly easy to get hold of,” says Rogers. “The majority of car thieves have no technical knowledge; they push a button on a box or wave an antenna, and the car unlocks.” The brainpower, he explains, is higher up the chain. “The people in the R&D supply chain that create and supply these criminal products are relatively untouchable, also involved in creating and selling criminal equipment such as fake fronts and skimming equipment for cash machines.”

“The tools themselves are not specifically designed for car theft,” adds Pilton. “The tools are most commonly used for communications systems and extending the range of wireless signals. However, just like a crowbar or screwdriver, criminals have re-purposed the tools. The pair committing the crime may not be the brains behind the operation,” he speculates. “They’re just the ones using the simple pre-configured tools handed to them.”

And this is why Reedman refuses to label this as car hacking. “It requires no skill. I suspect they do little more than watch videos online and buy the [relay] equipment. It’s trivial.” Hacking, argues Reedman, “requires a level of skill.”

Shockingly, there have been reports that children as young as 10 have been arrested for car theft, and children as young as 12 have been charged. Direct Line Motor Insurance reported just over a year ago that 1,156 people under the age of 18 were charged with vehicle theft over a three-year period. That’s more than one a day. It verifies the opinion that carrying out a relay attack is easy. “No doubt they learnt to drive playing Mario Kart and GTA V,” adds Cluley.

With automotive theft rising and keyless entry cars a favoured target due to their high value and ease of theft, manufacturers must take action. But, according to Wright, “the automotive industry is far behind most in protecting against technological attacks.”

I spoke to Mercedes-Benz for this article, asking them multiple questions regarding the theft of keyless vehicles and manufacturer accountability. A Mercedes-Benz spokesperson who did not wish to be named, tells me: “The security of our organisation, products and services is one of our top priorities in our research and development activities.”

The Mercedes spokesperson tells me that from mid-2019 onwards, the “facelift version of the GLC received a motion sensor in the vehicle key. This means that as soon as the key does not move for a certain time, the KEYLESS GO function is deactivated. This also means that range extension is no longer possible.” My car was a 2018 model, meaning it just missed out on the security benefit from this ‘facelift’.

“In addition, our keys offer the option to temporarily disable the KEYLESS GO function. This means the system can no longer be compromised even by a range extender.

“We are also working on anti-theft measures that can be used via the Mercedes me service…It offers the customer the option of deactivating the vehicle keys via the Mercedes me app if they are lost or stolen.” Mercedes declined to comment on why the option to disable KEYLESS GO isn’t presented to customers at the point of sale. They did, however, add:

“Another option is the GUARD 360° ‘stolen vehicle help’ function. Here, the customer can report the theft directly via the Mercedes me app, and the security centre of our certified partner will start locating the vehicle in coordination and cooperation with the authorities (police).”

“Car manufacturers continue to push ease-of-use functionality over security,” argues Pritchard. “ Theft of Range Rovers has risen so badly that JLR has had to introduce its own insurance offering as owners couldn’t afford premiums from standard insurers.”

According to Rogers, car manufacturers lack understanding of how the criminal ecosystem works and lack urgency in tackling and responding to new techniques. “There are plenty of solutions that can be deployed relatively quickly, but it appears there’s an old-style attitude to this problem, a reluctance to admit they exist.”

“Car manufacturers continue to push ease-of-use functionality over security” Chris Pritchard

Blame, Rogers adds, is often pushed onto the victims. “Owners are told they should have kept their keys away from the ground floor or blocked the car in with a second car that doesn’t have keyless ignition. This is plain wrong – the negligence is on the manufacturer. They know about the issue with their vehicles, but they’re mostly not doing anything about it. That said, the manufacturers are victims themselves. International law enforcement needs to do a better job clamping down on the international organised crime groups.”

Manufacturers are making some moves, though. Some have updated their key fobs with a movement sensor called an accelerometer to detect when they’ve been stationary for some time, entering sleep mode. “If the key is jangling about, it wakes up and can be used to unlock the car. If you’re tucked up in bed [and the key therefore still], a thief would not be able to relay the signal,” Cluley explains.

Some manufacturers use positioning technology and the ‘time of flight’ technique to confirm precisely how far the key is from the car before accepting the key’s response.

Making car owners aware of the risks of keyless entry at the point of sale seems like a quick win. Of course, car manufacturers will always put a positive spin on functionality, but empowering owners to make their own decisions regarding security versus convenience is a no-brainer.

“Car manufacturers have known about the risks for years, but some are taking a long time to roll out solutions. I imagine they’ll argue that changing anything about cars takes time and costs them money, of course!” adds Cluley.

From an ex-law enforcement perspective, Pilton suggests that responsibility for preventing car theft is shared and that collaboration between manufacturers, software developers, and regulatory bodies is essential. “Prevention could include minimum security standards for this technology and enabling car owners to make informed decisions.”

And then there’s the Criminal Justice Bill, introduced to UK Parliament in November 2023. The Bill will make it illegal to possess electronic devices that enable vehicle theft. The Bill’s factsheet says the Criminal Justice Bill’s measures include: “New powers to tackle serious and organised crime. Prohibiting articles used in serious crime…banning electronic devices such as signal jammers used in vehicle theft, and strengthening the operation of Serious Crime Prevention Orders.”

Rogers highlights the security research community’s concern. “It brings a chill on security research because of the potential for arrest while using [the technology] for research to prevent theft and find security flaws.”

The Bill has yet to pass through the House of Lords, so there’s still an opportunity for adjustment.

Criminals will always start with the low-hanging fruit. There’s no denying that relay attack car theft is an attractive target for criminals. The attack is easy to carry out: There’s no smashed glass, no alarms to raise suspicion. They simply drive off into the dead of the night. “It’s a low-risk crime that causes no damage to the stolen vehicle, which keeps the resale value high for the criminal,” explains Pritchard.

“While traditional key-based [car] systems are not without their weaknesses, keyless entry offers convenience at the potential cost of increased vulnerability to specific attack methods,” says Pilton.

It’s no wonder that Cluley tells me he is “very glad to have a dumb car.”

After sharing what happened to my car on social media, I’ve been inundated with similar tales and shared experiences. The scale of the problem is extensive, the success rate for recovering stolen cars is low, and successful prosecution is even rarer.

Due to the ‘smash and grab’ style of theft, success rates for finding and prosecuting perpetrators are “very poor,” bemoans Wright. They’re away before you notice, the tracking features disabled, and plates will have been changed before you call the police. It will likely be on a boat to another country before the day is done.”

Rogers recalls some “good stings where cars are sent abroad in containers or cut up for parts in ‘chop shops’. They’re only tackling the symptoms of the problem though – if you tackle the international criminal tool makers, the lower-level criminals will find it very difficult to operate.” If you’re unfamiliar with the term chop shop, it describes a place where stolen vehicles are disassembled and their parts either sold or used to rebuild other cars.

Pilton explains that he was involved in many pursuits, arresting offenders who had crashed and fled the car they had just stolen. “I investigated cases in which a car has seemingly disappeared overnight.” Identifying the criminals responsible can sometimes be exceptionally difficult,” he admits, “even impossible.”

He continues: “Combating this type of crime does present challenges for law enforcement. However, they do often succeed in locating cars, albeit the car may be burnt out following use in a crime, or it could just be recovering evidence that shows the stolen car has left the country. Prosecution is often difficult, though. Without finding the car in the UK, it is nearly impossible to directly pin a suspect to an individual car theft, but not impossible. What we see more frequently is organised crime groups leaving metaphorical breadcrumbs at each crime scene, allowing law enforcement to build a bigger picture and take targeted action against a group.”

It has been a month since my car was stolen, and there’s no sign of it or the other five vehicles that were taken at the same time. The detective assigned to my case told me that he suspects my car may have been stolen to rip cash machines out of walls, given its size and stature. But equally, it could now be a ‘citizen’ in another country or have undergone major plastic surgery in a chop shop. I’m informed that “the investigation continues to be progressed with a number of ongoing enquiries.”

That includes forensic analysis of some of the abandoned license plates recovered (including mine) and tracking information from the cars fitted with embedded SIMs. Do I hold out hope for vehicle recovery? Absolutely not. Even if it was recovered, it’s now the property of my insurance company. But I’ll hold onto some hope for both answers and prosecution.

On the night my car was stolen, I’d left my key in a drawer at the back of my house. I naively believed that storing it away from the front door (and, therefore, the driveway) would eliminate any chance of theft. Shamefully (given my line of work), I was not acutely aware of relay attacks nor the scale of the threat. I’m regretful that the usual cynicism I’ve inherited from an 18-year career in cybersecurity didn’t stretch to my car.

Now, of course, my eyes are wide open. I asked all my interviewees to share their advice for protecting keyless cars. There was one word that was consistently batted back at me: Faraday.

“Use a Faraday box or wallet to block any signal being sent or received by your car keys and get into the habit of always putting your keys in such a box when you return home,” advises Cluley. And make sure your spare key is tucked away in a Faraday box or wallet, too.

“The material used in the Faraday pouches deteriorates after a matter of weeks, leading to signal leakage” Dan Bulman

Reedman advises double-checking the effectiveness of your Faraday solution. “Check if you can unlock your car by pressing the unlock button from where you store your keys. If so, a one-way relay will work. If you can’t, a one-way relay will likely fail, but there are two-way relay attacks, so it depends.” He adds that not all Faraday enclosures are made equal; some will work and some won’t, but storing your keys far away from your car in a fully enclosed metal box is probably the easiest thing to do.”

The age-old advice of storing car keys away from your front door holds true also.

Rogers suggests turning off keyless ignition if possible, using a mechanical steering lock, and considering an OBDII port lock. “You can get these online; it makes it inconvenient for an attacker to plug into the diagnostic port once in your vehicle.”

Pilton adds that the power of sharing incidents on social media is not to be underestimated – raise awareness of the risks so people can act to protect their cars, he says.

At the tenth hour, just before I was due to press ‘publish’ on this article, I received a message from Dan Bulman, co-founder of KEYSHIELD. This new security device company claims to provide “100% protection against key cloning and relay theft.” The KEYSHIELD sleeve wraps around your key fob battery, preventing any signal from being emitted when the key is stationary. “It utilises motion sensor technology to disable the key battery power and signal when inactive for 20 seconds, preventing any risk of interception or cloning,” explains Bulman. He allowed me to trial the product on my new car, and I’m disappointed to report that it worked a little too well once installed, meaning I could not open my own car even with the keys and pressing unlock. The alarm was triggered each time I tried (and failed) to get into my own car. Perhaps it’s incompatible with my particular make and model of car. Bulman tells me they’ve not had this result before and are investigating.

Now that I’m all too familiar with the stakes, I’ll be taking the belt and braces method with my new car: a Faraday box, with a steering wheel lock for good measure. Cynicism officially restored and thriving.

So there you have it, the story of how my car was hacked and stolen while I slept, with a comprehensive explanation of how. Until car manufacturers stop glossing over the vulnerabilities of keyless cars and start educating owners about the security options available to them, I hope that articles like this will give a little bit of power back to car owners.